Table of Contents

ToggleThe Rise and Fall of the Coquette Aesthetic

In This Post

The coquette aesthetic once dominated Tumblr feeds and pastel mood boards — soft bows, ballet flats, muted pinks, and nostalgic femininity. But as TikTok monetized every trend and brands leaned in, the ethereal club of coquette girls started to feel less magical. This post explores how the coquette aesthetic rose, peaked, and lost its sparkle — and what it means for brands chasing aesthetics in the age of virality.

Today, the coquette aesthetic is more than just a mood board – it’s a case study in what happens when a soft, internet-born vibe becomes a monetized trend. This post isn’t just about bows and ballet flats; it’s about what coquette’s rise and fall can teach brands about using aesthetics and microtrends in their marketing. If you want the bigger picture on how these waves shape buying, scrolling and posting, we’ve broken down why microtrends matter in a separate guide.

The “coquette aesthetic” first popped onto my feed in 2014 – on Tumblr, where I was an active user, scrolling through angsty photos of the Arctic Monkeys and Lana del Rey lyrics.

Coqueticism is pretty much the same now as it was then – a smorgasbord of soft, muted pinks, hair ribbons, bows and ballet shoes. At its core, the coquette aesthetic is an expression of girlhood femininity (think Britney’s “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman” Y2K pop ballad).

The difference between the aesthetic ten years ago compared to today is that it was largely not-for-profit. It was a subsection of internet imagery that inspired a mood, more than a desire to obtain objects. Sure, I bought into the American Apparel circle skirt trend and big, clip in velvet hair bows that the trend championed, but it wasn’t a lifestyle as much as it was an inspiration.

Today, with TikTok shops and targeted Instagram ads, the coquette aesthetic poses a chicken-or-egg question: what came first, the coquette aesthetic or the coquette girl?

Coquette bows and soft style

On the rise of the aesthetic in 2024, ASA’s resident Gen Z designer and bonafide internet It girl Stella Green-Rhoades said:

“As an adult woman, everyone wanted to be a girl and accept girlhood. Everyone is getting . . . to that stage where you’re no longer a girl and [people] want to tie back to that.”

There’s a sense of time travel at play with the coquette aesthetic: if the price is right, you can be a girl again. Note the language surrounding the aesthetic online – No Doubt’s iconic “Just a Girl” was trending on TikTok, accompanied by videos of “girl dinner,” “girl room,” “girl core.”

The internet’s obsession with “girlhood” can be loosely connected to the release of the Barbie movie and ongoing discourse about fourth wave feminism – we are tired, we are told to buy X and Y to reverse ageing, we just want to crawl into bed and wake up 13 again (sorry, Jennifer Garner).

If you weave a ribbon through your ponytail, you still have to pay taxes (this was a bitter pill to swallow during tax season this year – I’m just a girl!).

We’ve seen a similar “aesthetic as identity” thing happen in BookTok, where certain covers and authors become status accessories as much as stories.

In this light, the coquette aesthetic benefited brands like Wildflower Cases, that boast hyper feminine designs, and Glossier, with its signature light pink and cherry red packaging, complementary branded stickers and hot pink bubble gum wrapping.

Throughout 2023, it felt like the trend would never end. So what happened?

For a while, the coquette aesthetic trend felt like a secret handshake: if you knew, you knew. It lived in bedroom mirrors, Instagram grids and pastel product design more than in obvious ad campaigns.

The cycles of fashion trends

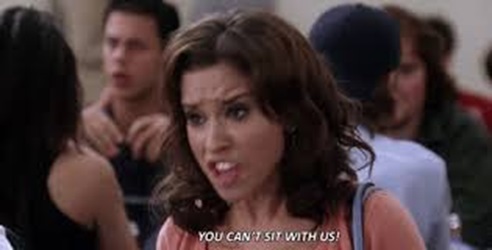

The trend being over doesn’t mean that it ceases to exist – it just means that it lost the magical, secret club feeling that I felt scrolling through TikTok and Instagram, seeing the legions of Lana and Addison Rae and glossy girls posting cute pics with im just a girl captions. That’s the reality of trend cycles in fashion and social media: once an aesthetic jumps from niche communities to big brand campaigns, it often shifts from “special” to “over” almost overnight.

The first time that I thought the coquette aesthetic was done was when I saw a TikTok by GO Transit. It was a clip of pink bows stuck to train cars and Presto refills.

Oh God, I remember thinking. I guess that’s over.

It’s the same energy we see when brands chase any trend or aesthetic that doesn’t fit their reality – the result feels cringe, not clever. Think about the Bon Appétit and Poppi scandals: great examples of what happens when brands chase vibes and virality without a grounded sense of who they are.

Coquette’s arc is a reminder that you can’t build your entire brand marketing strategy on whatever’s trending on TikTok that week.

But what was it about this video specifically that signalled the death of the trend’s authenticity?

For starters, it was the mis-handled application of a concept by a corporation that defies the ethos of girlhood.

Girlhood is free of responsibility and calls to mind a magical dreamworld where there are no problems and everything is easy. GO Transit, with its unrelenting fare inspectors and the threat of danger that is being a woman on public transit, is not conducive to this aesthetic.

Not only is it not conducive, it undermines the integrity of both parties: the sanctity of the hair bow and what it stands for (remember in Barbie when the world starts turning and she sees generations of girls grow into women), and the severity of the issues plaguing public transit systems.

Moreover, GO Transit’s TikTok represents the cheugy, slightly out of touch brands that try to harness the raw power and authenticity of trends sparked by real people creating authentic content online. It’s always obvious when a brand reaches for a sense of connection with an audience that it simply should not try to connect with, as it will not play out well. Or rather, it’s extremely clear in a way that is *cringe* when a brand’s marketing team tries to take on an aesthetic that is not applicable to the ethos of the company itself.

What the coquette aesthetic teaches brands

If you zoom out from the bows and ballet flats, the coquette aesthetic offers a few clear lessons for brands:

- Not every aesthetic is for you. If your product or audience doesn’t naturally connect with girlhood softness or nostalgia, forcing it will read as costume, not creativity.

- Authenticity beats bandwagons. Coquette felt magical when it came from real girls in real bedrooms; it felt hollow when it showed up on train cars and corporate feeds.

- Microtrends move fast. By the time a vibe like coquette hits mass campaigns, the internet’s already looking for the next thing. Build your brand around values and stories that last longer than a single aesthetic.

- Take care with “girlhood” in marketing. Girlhood isn’t just a colour palette; it’s tied to real emotions and experiences. Treat it with more nuance than just slapping bows on your product.

Done well, playing with aesthetics like coquette can be a fun way to signal that you “get” your audience. Done poorly, it’s the quickest route to feeling dated, cheugy and out of touch.

Where the Coquette Aesthetic Goes Next

The rise and fall of the coquette aesthetic speaks to the ephemerality of trend cycles, and the essential question that brands attempting to co-opt trends and aesthetics should ask: can we really sit with them?

It’s questionable – but you can sit with us. At ASA, we consider ourselves TikTok experts (and we’ve never put a bow on a bus). As a digital marketing agency in Toronto and creative agency, we help brands tap into trends without coming across as outdated or “cheugy.” Looking to hone your brand’s voice and play with aesthetics like coquette in a way that actually fits? Check out our services – or get in touch to chat.

FAQs

The coquette aesthetic is a feminine way of dressing, styling and presenting oneself that emphasises a return to girlhood innocence. Its signature elements include ballet-style shoes and skirts, hair bows, soft shades of pink and muted pastels. Think of Sofia Coppola’s movies and Petra Collins’ photography.

Q: Why have trend cycles gotten shorter?

A: The short answer? Technology and social media. Trend cycles have five phases – introduction, rise, peak, decline and obsolescence. The virality of trends online, coupled with faster-than-ever consumer cycles and rapid turnover, have dramatically shortened the length of trends. Online, we’re always looking for the new best thing – it’s giving Regina George.

In internet terms, it’s a whole coquette aesthetic meaning: not just clothes, but a mood and way of presenting yourself online.

This is a grey area – sometimes, brands see unexpected success when they take up trends that may seem outside of their comfort zone. Take Duolingo’s TikTok for example – who would have thought that bringing the bird logo to your iPhone screen would take on such a life of its own?

From a marketing standpoint, that means microtrends burn out faster than ever – which is why brands need to be choosy about which ones they attach themselves to.

Unlike trends, social issues, however, should only be taken on by brands in meaningful, thoughtful and compelling ways – in our opinion! Our rule of thumb: don’t hop on the social issues bandwagon unless you’re prepared to back it up with aligned values or action.

The key is knowing whether a trend supports your long-term brand story or is just a fun one-off moment for social media marketing.

Coquette’s rise and fall is a reminder that aesthetics born in niche online spaces don’t stay niche for long. For brands, the lesson is to treat trends like coquette as inspiration, not identity. If the coquette aesthetic genuinely overlaps with your audience and values, you can borrow its language and visuals in a subtle way; if it doesn’t, it’s better to admire from a distance than force it into your feed.

For more on how to work with fast-moving trends, see our guide on microtrends in marketing.